Crystal skull

Crystal skulls are human skull hardstone carvings made of clear or milky white quartz (also called "rock crystal"), claimed to be pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artifacts by their alleged finders; however, these claims have been refuted for all of the specimens made available for scientific studies. The results of these studies demonstrated that those examined were manufactured in the mid-19th century or later, almost certainly in Europe, during a time when interest in ancient culture abounded.[1][2][3] The skulls appear to have been crafted in Germany, quite likely at workshops in the town of Idar-Oberstein, which was renowned for crafting objects made from imported Brazilian quartz in the late 19th century.[2][4]

Despite some claims presented in an assortment of popularizing literature, legends of crystal skulls with mystical powers do not figure in genuine Mesoamerican or other Native American mythologies and spiritual accounts.[5] The skulls are often claimed to exhibit paranormal phenomena by some members of the New Age movement, and have often been portrayed as such in fiction. Crystal skulls have been a popular subject appearing in numerous science fiction television series, novels, films, and video games.

Collections

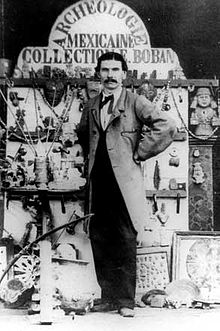

[edit]Trade in fake pre-Columbian artifacts developed during the late 19th century to the extent that in 1886, Smithsonian archaeologist William Henry Holmes wrote an article called "The Trade in Spurious Mexican Antiquities" for Science.[6] Although museums had acquired skulls earlier, it was Eugène Boban, an antiquities dealer who opened his shop in Paris in 1870, who is most associated with 19th-century museum collections of crystal skulls. Most of Boban's collection, including three crystal skulls, was sold to the ethnographer Alphonse Pinart, who donated the collection to the Trocadéro Museum, which later became the Musée de l'Homme.

Research

[edit]Many crystal skulls are claimed to be pre-Columbian, usually attributed to the Aztec or Maya civilizations. Mesoamerican art has numerous representations of skulls, but none of the skulls in museum collections come from documented excavations.[7] Research carried out on several crystal skulls at the British Museum in 1967, 1996 and 2004 shows that the indented lines marking the teeth (for these skulls had no separate jawbone, unlike the Mitchell-Hedges skull) were carved using jeweler's equipment (rotary tools) developed in the 19th century, making a pre-Columbian origin untenable.[8]

The type of crystal was determined by examination of chlorite inclusions.[9] It is only found in Madagascar and Brazil, and thus unobtainable or unknown within pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The study concluded that the skulls were crafted in the 19th century in Germany, quite likely at workshops in the town of Idar-Oberstein, which was renowned for crafting objects made from imported Brazilian quartz in the late 19th century.[4]

It has been established that the crystal skulls in the British Museum and Paris's Musée de l'Homme[10] were originally sold by the French antiquities dealer Eugène Boban, who was operating in Mexico City between 1860 and 1880.[11] The British Museum crystal skull transited through New York's Tiffany & Co., while the Musée de l'Homme's crystal skull was donated by Alphonse Pinart, an ethnographer who had bought it from Boban.

In 1992 the Smithsonian Institution investigated a crystal skull provided by an anonymous source; the source claimed to have purchased it in Mexico City in 1960, and that it was of Aztec origin. The investigation concluded that this skull also was made recently. According to the Smithsonian, Boban acquired his crystal skulls from sources in Germany, aligning with conclusions made by the British Museum.[12]

The Journal of Archaeological Science published a detailed study by the British Museum and the Smithsonian in May 2008.[13] Using electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography, a team of British and American researchers found that the British Museum skull was worked with a harsh abrasive substance such as corundum or diamond, and shaped using a rotary disc tool made from some suitable metal. The Smithsonian specimen had been worked with a different abrasive, namely silicon carbide (carborundum), a silicon-carbon compound which is a synthetic substance manufactured using modern industrial techniques.[14] Since the synthesis of carborundum dates only to the 1890s and its wider availability to the 20th century, the researchers concluded "[t]he suggestion is that it was made in the 1950s or later".[15]

Individual skulls

[edit]British Museum skull

[edit]The crystal skull of the British Museum first appeared in 1881, in the shop of the Paris antiquarian, Eugène Boban. Its origin was not stated in his catalogue of the time. He is said to have tried to sell it to Mexico's national museum as an Aztec artifact, but was unsuccessful. Boban later moved his business to New York City, where the skull was sold to George H. Sisson. It was exhibited at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in New York City in 1887 by George F. Kunz.[16] It was sold at auction, and bought by Tiffany and Co., who later sold it at cost to the British Museum in 1897.[17][2] This skull is very similar to the Mitchell-Hedges skull, although it is less detailed and does not have a movable lower jaw.[18]

The British Museum catalogues the skull's provenance as "probably European, 19th century AD"[17] and describes it as "not an authentic pre-Columbian artefact".[19][20] It has been established that this skull was made with modern tools, and that it is not authentic.[21]

Mitchell-Hedges skull

[edit]Perhaps the most famous and enigmatic skull was allegedly discovered in 1924 by Anna Mitchell-Hedges, adopted daughter of British adventurer and popular author F. A. Mitchell-Hedges. It is the subject of a video documentary made in 1990, Crystal Skull of Lubaantun.[22] It was examined and described by Smithsonian researchers as "very nearly a replica of the British Museum skull – almost exactly the same shape, but with more detailed modeling of the eyes and the teeth".[23]

Mitchell-Hedges claimed that she found the skull buried under a collapsed altar inside a temple in Lubaantun, in British Honduras, now Belize.[24] As far as can be ascertained, F.A. Mitchell-Hedges himself made no mention of the alleged discovery in any of his writings on Lubaantun. Others present at the time of the excavation recorded neither the skull's discovery nor Anna's presence at the dig.[25] Recent evidence has come to light showing that F.A. Mitchell-Hedges purchased the skull at a Sotheby's auction in London on October 15, 1943, from London art dealer Sydney Burney.[26] In December 1943, F. A. Mitchell-Hedges disclosed his purchase of the skull in a letter to his brother, stating plainly that he acquired it from Burney.[26][27]

The skull is made from a block of clear quartz about the size of a small human cranium, measuring some 5 inches (13 cm) high, 7 inches (18 cm) long and 5 inches (13 cm) wide. The lower jaw is detached. In the early 1970s it came under the temporary care of freelance art restorer Frank Dorland, who claimed upon inspecting it that it had been "carved" with total disregard to the natural crystal axis, and without the use of metal tools. Dorland reported being unable to find any tell-tale scratch marks, except for traces of mechanical grinding on the teeth, and he speculated that it was first chiseled into rough form, probably using diamonds, and the finer shaping, grinding and polishing was achieved through the use of sand over a period of 150 to 300 years. He said it could be up to 12,000 years old. Although various claims have been made over the years regarding the skull's physical properties, such as an allegedly constant temperature of 70 °F (21 °C), Dorland reported that there was no difference in properties between it and other natural quartz crystals.[28]

While in Dorland's care the skull came to the attention of writer Richard Garvin, at the time working at an advertising agency where he supervised Hewlett-Packard's advertising account. Garvin made arrangements for the skull to be examined at Hewlett-Packard's crystal laboratories in Santa Clara, California, where it was subjected to several tests. The labs determined only that it was not a composite as Dorland had supposed, but that it was fashioned from a single crystal of quartz.[29] The laboratory test also established that the lower jaw had been fashioned from the same left-handed growing crystal as the rest of the skull.[30] No investigation was made by Hewlett-Packard as to its method of manufacture or dating.[31]

As well as the traces of mechanical grinding on the teeth noted by Dorland,[32] Mayanist archaeologist Norman Hammond reported that the holes (presumed to be intended for support pegs) showed signs of being made by drilling with metal.[33] Anna Mitchell-Hedges refused subsequent requests to submit the skull for further scientific testing.[34]

The earliest published reference to the skull is the July 1936 issue of the British anthropological journal Man, where it is described as being in the possession of Sydney Burney, a London art dealer who was said to have owned it since 1933,[35] and from whom evidence suggests F.A. Mitchell-Hedges purchased it.[26]

F. A. Mitchell-Hedges mentioned the skull only briefly in the first edition of his autobiography, Danger My Ally (1954), without specifying where or by whom it was found.[36] He merely claimed that "it is at least 3,600 years old and according to legend it was used by the High Priest of the Maya when he was performing esoteric rites. It is said that when he willed death with the help of the skull, death invariably followed".[37] All subsequent editions of Danger My Ally omitted mention of the skull entirely.[34]

In a 1970 letter Anna also stated that she was "told by the few remaining Maya that the skull was used by the high priest to will death".[38] For this reason, the artifact is sometimes referred to as "The Skull of Doom". Anna Mitchell-Hedges toured with the skull from 1967 exhibiting it on a pay-per-view basis.[39] Somewhere between 1988 and 1990 she toured with the skull. She continued to grant interviews about the artifact until her death.

In her last eight years, Anna Mitchell-Hedges lived in Chesterton, Indiana, with Bill Homann, whom she married in 2002. She died on April 11, 2007. Since that time the Mitchell-Hedges Skull has been owned by Homann. He continues to believe in its mystical properties.[40]

In November 2007, Homann took the skull to the office of anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh, in the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History for examination.[41] Walsh carried out a detailed examination of the skull using ultraviolet light, a high-powered light microscope, and computerized tomography. Homann took the skull to the museum again in 2008 so it could be filmed for a Smithsonian Networks documentary, Legend of the Crystal Skull, and on this occasion, Walsh was able to take two sets of silicone molds of surface tool marks for scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis. The SEM micrographs revealed evidence that the crystal had been worked with a high speed, hard metal rotary tool coated with a hard abrasive, such as diamond. Walsh's extensive research on artifacts from Mexico and Central America showed that pre-contact artisans carved stone by abrading the surface with stone or wooden tools, and in later pre-Columbian times, copper tools, in combination with a variety of abrasive sands or pulverized stone. These examinations led Walsh to the conclusion that the skull was probably carved in the 1930s, and was most likely based on the British Museum skull which had been exhibited fairly continuously from 1898.[41]

In the National Geographic Channel documentary "The Truth Behind the Crystal Skulls", forensic artist Gloria Nusse performed a forensic facial reconstruction over a replica of the skull. According to Nusse, the resulting face had female and European characteristics. As it was hypothesized that the Crystal Skull was a replica of an actual human skull, the conclusion was that it could not have been created by ancient Americans.[42]

Paris skull

[edit]

The largest of the three skulls sold by Eugène Boban to Alphonse Pinart (sometimes called the Paris Skull), about 10 cm (4 in) high, has a hole drilled vertically through its center.[43] It is part of a collection held at the Musée du Quai Branly, and was subjected to scientific tests carried out in 2007–08 by France's national Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums in France, or C2RMF). After a series of analyses carried out over three months, C2RMF engineers concluded that it was "certainly not pre-Columbian, it shows traces of polishing and abrasion by modern tools".[44][full citation needed] Particle accelerator tests also revealed occluded traces of water that were dated to the 19th century, and the Quai Branly released a statement that the tests "seem to indicate that it was made late in the 19th century".[45][full citation needed]

In 2009 the C2RMF researchers published results of further investigations to establish when the Paris skull had been carved. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis indicated the use of lapidary machine tools in its carving. The results of a new dating technique known as quartz hydration dating (QHD) demonstrated that the Paris skull had been carved later than a reference quartz specimen artifact, known to have been cut in 1740. The researchers conclude that the SEM and QHD results combined with the skull's known provenance indicate it was carved in the 18th or 19th century.[46]

Smithsonian Skull

[edit]The "Smithsonian Skull", Catalogue No. A562841-0 in the collections of the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, was mailed to the Smithsonian Institution anonymously in 1992, and was claimed to be an Aztec object by its donor and was purportedly from the collection of Porfirio Diaz. It is the largest of the skulls, with a weight of 31 pounds (14 kg) and a height of 15 inches (38 cm). It was carved using carborundum, a modern abrasive. It has been displayed as a modern fake at the National Museum of Natural History.[47]

Paranormal claims and spiritual associations

[edit]Some individuals believe in the paranormal claim that crystal skulls can produce a variety of miracles. Anna Mitchell-Hedges claimed that the skull she allegedly discovered could cause visions and cure cancer, that she once used its magical properties to kill a man, and that in another instance, she saw in it a premonition of the John F. Kennedy assassination.[48]

In the 1931 play The Satin Slipper by Paul Claudel, King Philip II of Spain uses "a death's head made from a single piece of rock crystal", lit by "a ray of the setting sun", to see the defeat of the Spanish Armada in its attack on the Kingdom of England.[49]

Claims of the healing and supernatural powers of crystal skulls have had no support in the scientific community, which has found no evidence of any unusual phenomena associated with the skulls nor any reason for further investigation, other than the confirmation of their provenance and method of manufacture.[50]

Another novel and historically unfounded speculation ties in the legend of the crystal skulls with the completion of the previous Maya calendar b'ak'tun-cycle on December 21, 2012, claiming the re-uniting of the thirteen mystical skulls will forestall a catastrophe allegedly predicted or implied by the ending of this calendar (see 2012 phenomenon). An airing of this claim appeared (among an assortment of others made) in The Mystery of the Crystal Skulls,[51] a 2008 program produced for the Sci Fi Channel in May and shown on Discovery Channel Canada in June. Interviewees included Richard Hoagland, who attempted to link the skulls and the Maya to life on Mars, and David Hatcher Childress, proponent of lost Atlantean civilizations and anti-gravity claims.

Crystal skulls are also referred to by author Drunvalo Melchizedek in his book Serpent of Light.[52] He writes that he came across indigenous Mayan descendants in possession of crystal skulls at ceremonies at temples in the Yucatán, which he writes contained souls of ancient Mayans who had entered the skulls to await the time when their ancient knowledge would once again be required.

The alleged associations and origins of crystal skull mythology in Native American spiritual lore, as advanced by neoshamanic writers such as Jamie Sams, are similarly discounted.[53] Instead, as Philip Jenkins notes, crystal skull mythology may be traced back to the "baroque legends" initially spread by F.A. Mitchell-Hedges, and then afterwards taken up:

By the 1970s, the crystal skulls [had] entered New Age mythology as potent relics of ancient Atlantis, and they even acquired a canonical number: there were exactly thirteen skulls.

None of this would have anything to do with North American Indian matters, if the skulls had not attracted the attention of some of the most active New Age writers.[54]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Crystal Skulls". National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ a b c British Museum (n.d.-b).

- ^ Jenkins (2004, p. 217), Sax et al. (2008), Smith (2005), Walsh (1997; 2008).

- ^ a b Craddock (2009, p. 415).

- ^ Aldred (2000, passim.); Jenkins (2004, pp. 218–219). In this latter work, Philip Jenkins, former Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies and subsequent endowed Professor of Humanities at PSU, writes that crystal skulls are among the more obvious of examples where the association with Native spirituality is a "historically recent" and "artificial" synthesis. These are "products of a generation of creative spiritual entrepreneurs" that do not "[represent] the practice of any historical community".

- ^ Holmes (1886)

- ^ Walsh (2008)

- ^ Craddock (2009, p. 415)

- ^

"These iron chlorite inclusions found in the British Museum's fake skull are found only in quartz from Brazil or Madagascar but not Mexico;

from google (crystal skull fakes) result 1". - ^ The specimen at the Musée de l'Homme is half-sized.

- ^ See "The mystery of the British Museum's crystal skull is solved. It's a fake", in The Independent (Connor 2005). See also the museum's issued public statement on its crystal skull (British Museum (n.d.-c).

- ^ See the account given by Smithsonian anthropologist Jane Walsh of her joint investigations with British Museum's materials scientist Margaret Sax, which ascertained the crystal skull specimens to be 19th century fakes, in Smith (2005). See also Walsh (1997).

- ^ Sax et al. (2008)

- ^ Carborundum occurs naturally only in minute amounts in the extremely rare mineral moissanite, first identified in a meteorite in 1893. See summary of the discovery and history of silicon carbide in Kelly (n.d.)

- ^ See reportage of the study in Rincon (2008), and the study itself in Sax et al. (2008).

- ^ "A Great Labor Problem. It Receives Attention from the Scientists. They devote attention, too, to a beautiful adze and a mysterious crystal skull" (PDF). New York Times. No. August 13. 1887. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ a b British Museum (n.d.-a).

- ^ Digby (1936)

- ^ British Museum (n.d.-c).

- ^ See also articles on the investigations which established it to be a fake, in Connor (2005), Jury (2005), Smith (2005), and Walsh (1997, 2008).

- ^ Rincon (2008), Sax et al. (2008)

- ^ "Crystal Skull of Labaantun (1990)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ Walsh (2008). See also the 1936 debate on its resemblance to the British Museum skull, in Digby (1936) and Morant (1936), passim.

- ^ See Garvin (1973, caption to photo 25); also Nickell (2007, p. 67).

- ^ Nickell (2007, pp. 68–69)

- ^ a b c Walsh, Jane MacLaren (May 27, 2010). "The Skull of Doom". Archaeology Magazine. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ National Geographic Society, "The Truth Behind: The Crystal Skulls" (2011), a broadcast which includes an interview with Dr. Jane Walsh, Smithsonian Institution: "It was sold at auction, at Sotheby's, to Frederick Mitchell-Hedges, so he didn't get it at Lubaantun, he didn't dig it up".

- ^ Dorland, in a May 1983 letter to Joe Nickell, cited in Nickell (2007, p. 70).

- ^ See Garvin (1973, pp. 75–76), also Hewlett-Packard (1971, p. 9). The test involved immersing the skull in a liquid (benzyl alcohol) with the same diffraction coefficient and viewing it under polarized light.

- ^ Garvin (1973, pp. 75–76); Hewlett-Packard (1971, p. 9).

- ^ Hewlett-Packard (1971, p. 10).

- ^ Garvin (1973, p. 84); also cited in Nickell (2007, p. 70).

- ^ Hammond, in a May 1983 letter to Nickell, cited in Nickell (2007, p. 70). See also Hammond's recounting of his meeting with Anna Mitchell-Hedges and the skull in an article written for The Times, in Hammond (2008).

- ^ a b Nickell (2007, p. 69)

- ^ See Morant (1936, p. 105), and comments in Digby (1936). See also discussion of the prior ownership in Nickell (2007, p. 69).

- ^ See Mitchell-Hedges (1954, pp. 240–243); also description of same in the chapter "Riddle of the Crystal Skulls", in Nickell (2007, pp. 67–73).

- ^ Mitchell-Hedges' quote, as reproduced in Nickell (2007, p. 67).

- ^ Garvin (1973, p. 93)

- ^ Hammond (2008)

- ^ Stelzer, C.D. (2008-06-12). "The kingdom of the crystal skull". Illinois Times. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ a b Walsh, Jane MacLaren (May 27, 2010). "The Skull of Doom:Under the Microscope". Archaeology Magazine. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ The Truth Behind the Crystal Skulls (Documentary). National Geographic Channel: The Truth Behind. 2013. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011.

- ^ Kunz (1890, pp. 285–286), see description in "Ch. XIV: Mexico & Central America"

- ^ Quote reported by Agence France-Presse, see Rosemberg (2008).

- ^ Quote reported by Agence France-Presse, see Rosemberg (2008). See also Walsh (2008).

- ^ Calligaro et al. (2009, abstract)

- ^ Edwards, Owen (May 30, 2008). "The Smithsonian's Crystal Skull". Smithsonian Museum. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Various authors. "The Crystal Skulls" Skeptic magazine. Vol. 14, No. 2. 2008. Problem . 89.

- ^ Claudel, Paul. The Satin Slipper. Translated John O'Connor and Paul Claudel. London: Sheed & Ward, 1931, pp. 243–244. Originally published as Le Soulier de Satin (Paris: Nouvelle Revue Française).

- ^ See Nickell (2007, pp. 67–73); Smith (2005); Walsh (1997; 2008).

- ^ John Schriber (Executive Producer). Kevin Huffman, Erin McGarry, Andrew Rothstein and Andrea Skipper (Producers). Jayme Roy (Director of Photography). Lester Holt (Presenter) (May 2008). The Mystery of the Crystal Skulls (television program). New York: Peacock Productions (NBC), in association with the Sci Fi Channel. Archived from the original on 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ Serpent of Light – Beyond 2012, ISBN 1578634016

- ^ See discussion of the various claims put forward by Sams, Kenneth Meadows, Harley Swift Deer Reagan and others concerning crystal skulls, extraterrestrials, and Native American lore, in Jenkins (2004, pp. 215–218).

- ^ Quotation from Jenkins (2004, pp. 217–218).

References

[edit]- Aldred, Lisa (Summer 2000). "Plastic Shamans and Astroturf Sun Dances: New Age Commercialization of Native American Spirituality". American Indian Quarterly. 24 (3): 329–352. doi:10.1353/aiq.2000.0001. ISSN 0095-182X. JSTOR 1185908. OCLC 184746956. PMID 17086676. S2CID 6012903.

- British Museum. "Rock crystal skull". Explore: Highlights. Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- British Museum. "Study of two large crystal skulls in the collections of the British Museum and the Smithsonian Institution". Explore: Articles. Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- British Museum. "The crystal skull". News and press releases: Statements. Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- Calligaro, Thomas; Yvan Coquinot; Ina Reiche; Jacques Castaing; Joseph Salomon; Gerard Ferrand; Yves Le Fur (March 2009). "Dating study of two rock crystal carvings by surface microtopography and by ion beam analyses of hydrogen". Applied Physics A: Materials Science & Processing. 94 (4): 871–878. Bibcode:2009ApPhA..94..871C. doi:10.1007/s00339-008-5018-9. ISSN 0947-8396. OCLC 311109270. S2CID 18204055.

- Connor, Steve (2005-01-07). "The mystery of the British Museum's crystal skull is solved. It's a fake". The Independent. London: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Craddock, Paul (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Oxford, UK and Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0750642057. OCLC 127107601.

- Digby, Adrian (July 1936). "Comments on the Morphological Comparison of Two Crystal Skulls". Man. 36: 107–109. doi:10.2307/2789342. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2789342. OCLC 42646610.

- Garvin, Richard (1973). The Crystal Skull: The Story of the Mystery, Myth and Magic of the Mitchell-Hedges Crystal Skull Discovered in a Lost Mayan City During a Search for Atlantis. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385094566. OCLC 553587.

- Hammond, Norman (2008-04-28). "Secrets of the crystal skulls are lost in the mists of forgery". The Times. London: News International. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- Hewlett-Packard (magazine editorial staff) (February 1971). "History or hokum? Santa Clara's crystals lab helps tackle the case of the hard-headed Honduran." (PDF online facsimile at HParchive). Measure (Staff Magazine). Palo Alto, CA: Hewlett-Packard: 8–10. Retrieved 2008-04-11.[permanent dead link]

- Hidalgo, Pablo (2008-04-07). "The Lost Chronicles of Young Indiana Jones". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- Holmes, William H. (1886-02-19). "The trade in spurious Mexican antiquities". Science. New Series. ns-7 (159S): 170–172. doi:10.1126/science.ns-7.159S.170. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 213776464. PMID 17787662. S2CID 5254735.

- Hruby, Zachary (May 2008). "Critical Notes on "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull"". Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb. Archived from the original on 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- Jenkins, Philip (2004). Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195161151. OCLC 54074085.

- Jury, Louise (2005-05-24). "Art market scandal: British Museum expert highlights growing problem of fake antiquities". The Independent. London: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Kelly, Jim. "A brief history of SiC". Industrial Materials Group, University College London. Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- Kunz, George Frederick (1890). Gems and precious stones of North America: A popular description of their occurrence, value, history, archæology, and of the collections in which they exist, also a chapter on pearls, and on remarkable foreign gems owned in the United States. Illustrated with eight colored plates and numerous minor engravings. New York: The Scientific Publishing Company. OCLC 3257032.

- McCoy, Max (1995). Indiana Jones and the Philosopher's Stone. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553561968. OCLC 32417516.

- McCoy, Max (1996). Indiana Jones and the Dinosaur Eggs. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553561937. OCLC 34306261.

- McCoy, Max (1997). Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553561951. OCLC 36380785.

- McCoy, Max (1999). Indiana Jones and the Secret of the Sphinx. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553561975. OCLC 40775168.

- Mitchell-Hedges, F.A. (1954). Danger My Ally. London: Elek Books. OCLC 2117472.

- Morant, G.M. (July 1936). "A Morphological Comparison of Two Crystal Skulls". Man. 36: 105–107. doi:10.2307/2789341. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2789341. OCLC 42646610.

- Nickell, Joe (2007). Adventures in Paranormal Investigation. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813124674. OCLC 137305722.

- Olivier, Guilhem (2003). Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, "Lord of the Smoking Mirror". Michel Besson (trans.) (Translation of: Moqueries et métamorphoses d'un dieu aztèque (Paris : Institut d'ethnologie, Musée de l'homme, 1997) ed.). Boulder: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0870817458. OCLC 52334747.

- Rincon, Paul (2008-05-22). "Crystal skulls 'are modern fakes'". Science/Nature. BBC News online. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- Rosemberg, Claire (2008-04-18). "Skullduggery, Indiana Jones? Museum says crystal skull not Aztec". AFP. Archived from the original on 2013-04-01. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- Sax, Margaret; Jane M. Walsh; Ian C. Freestone; Andrew H. Rankin; Nigel D. Meeks (October 2008). "The origin of two purportedly pre-Columbian Mexican crystal skulls". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (10): 2751–2760. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35.2751S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.05.007. ISSN 1095-9238. OCLC 36982975.

- Smith, Donald (2005). "With a high-tech microscope, scientist exposes hoax of 'ancient' crystal skulls". Inside Smithsonian Research. 9 (Summer). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Office of Public Affairs. OCLC 52905641. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- Taube, Karl A. (1992). "The iconography of mirrors at Teotihuacan". In Janet Catherine Berlo (ed.). Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 8th and 9th October 1988. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 169–204. ISBN 978-0884022053. OCLC 25547129.

- Walsh, Jane MacLaren (1997). "Crystal skulls and other problems: or, "don't look it in the eye"". In Amy Henderson; Adrienne L. Kaeppler (eds.). Exhibiting Dilemmas: Issues of Representation at the Smithsonian. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1560986904. OCLC 34598037.

- Walsh, Jane MacLaren (Spring 2005). "What is Real? A New Look at PreColumbian Mesoamerican Collections" (PDF online publication). AnthroNotes: Museum of Natural History Publication for Educators. 26 (1): 1–7, 17–19. doi:10.5479/10088/22411. ISSN 1548-6680. OCLC 8029636.

- Walsh, Jane MacLaren (May–June 2008). "Legend of the Crystal Skulls". Archaeology. 61 (3): 36–41. ISSN 0003-8113. OCLC 1481828. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

External links

[edit]- Dunning, Brian (April 29, 2008). "Skeptoid #98: The Crystal Skull: Mystical, or Modern?". Skeptoid.

- At the British Museum: BM https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Am1898-1

- Crystal skull

- 1881 archaeological discoveries

- 1881 sculptures

- 19th-century hoaxes

- Anonymous works

- Archaeological forgeries

- Collection of the Smithsonian Institution

- Birkenfeld (district)

- Prehistory and Europe objects in the British Museum

- Culture of Rhineland-Palatinate

- German sculpture

- Hardstone carving

- Pseudoarchaeology

- Quartz

- Skulls in art